Deadweight Loss in Belgium

Below is a structured, concrete analysis of Deadweight Loss in Belgium, presented in English, with sector-by-sector estimates, conceptual graphs, and clear economic mechanisms. The figures are order-of-magnitude estimates, not exact measurements, which is standard for deadweight loss analysis.

Deadweight Loss in Belgium — Sectoral Analysis

1. Labor Market (Largest Source)

Mechanism

Very high tax wedge on labor (income tax + social contributions).

Large gap between employer cost and net take-home pay.

Reduces:

labor supply (hours worked, participation),

labor demand (job creation),

formal employment (pushes activity into grey economy).

Indicative magnitude

Belgium tax wedge ≈ 52–55% (among highest in OECD).

Empirical literature suggests deadweight loss ≈ 20–30% of tax revenue on labor.

Estimated annual deadweight loss

Labor tax revenue ≈ €150–170 bn

Deadweight loss: €30–45 bn/year

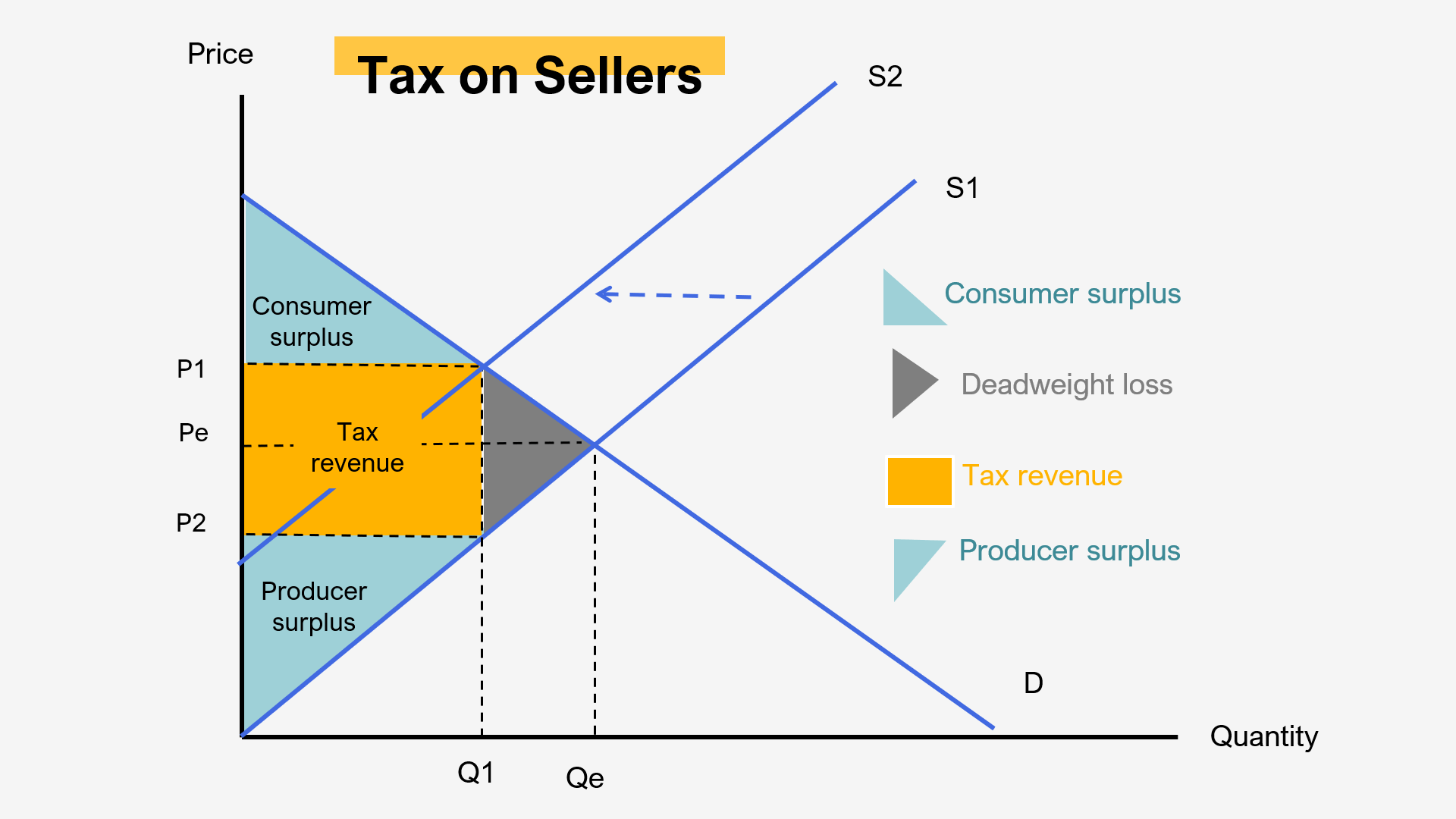

Graph (conceptual)

Standard supply–demand for labor.

Tax shifts wedge → quantity of labor falls.

Triangle between old and new equilibrium = deadweight loss.

2. Housing & Rental Market

Mechanism

Rent regulation, slow permitting, zoning restrictions.

Supply reacts weakly to demand.

Result:

fewer rental units,

higher prices,

misallocation (people stay in suboptimal housing).

Estimated annual deadweight loss

Based on EU housing efficiency studies: 0.3–0.7% of GDP

Belgium GDP ≈ €600 bn

Deadweight loss: €2–4 bn/year

Graph

Supply curve artificially inelastic.

Price ceiling or planning constraint creates shortage.

Lost transactions = deadweight loss.

3. Business Regulation & Administrative Burden (SMEs)

Mechanism

High compliance costs (VAT complexity, payroll rules, reporting).

Entry barriers for SMEs and startups.

Fewer firms enter → less competition → lower output.

Estimated annual deadweight loss

Conservative OECD-style estimate: 0.5–1.0% of GDP

€3–6 bn/year

Graph

Regulation shifts supply curve upward.

Higher prices, lower quantity.

Triangle of unrealized trades.

4. Capital & Entrepreneurship (Risk and Returns)

Mechanism

High effective taxation on:

dividends,

capital gains (direct and indirect),

self-employment income.

Discourages:

scaling businesses,

reinvestment,

risk-taking.

Estimated annual deadweight loss

Typically 0.3–0.6% of GDP

€2–4 bn/year

5. Informal / Shadow Economy (Symptom-Based Loss)

Mechanism

Activity moves outside formal system due to:

taxes,

regulation,

rigidity.

Even if activity exists, efficiency is lower:

no scale,

no financing,

legal risk.

Estimated annual deadweight loss

Shadow economy ≈ 15% of GDP

Efficiency loss estimated at ~20–25%

€15–20 bn/year

(Note: not all shadow activity is deadweight loss; this reflects efficiency loss, not total volume.)

Summary Table (Annual Estimates)

| Sector | Estimated Deadweight Loss |

|---|---|

| Labor market | €30–45 bn |

| Housing & rental | €2–4 bn |

| Business regulation | €3–6 bn |

| Capital & entrepreneurship | €2–4 bn |

| Informal economy inefficiency | €15–20 bn |

| Total (order of magnitude) | €50–75 bn/year |

➡ Roughly 8–12% of Belgian GDP in lost economic efficiency.

Important Clarifications

Deadweight loss ≠ government spending

Taxes transferred to the state are not deadweight loss.

Only destroyed surplus counts.

These losses are structural, not cyclical.

Even small tax or regulatory changes can reduce deadweight loss non-linearly.

Strategic Interpretation

From a policy or business perspective:

Belgium trades equity and stability for efficiency.

The system is resilient but not optimal at the margin.

Marginal reforms (lower labor taxes at the bottom, simpler SME rules) yield disproportionately large gains.

One-Sentence Executive Summary

Belgium likely incurs €50–75 billion per year in deadweight loss, primarily from labor taxation and regulatory rigidity—value that is neither earned by workers, firms, nor the state, but simply never created.

Policy reform scenarios

1) Revenue-neutral “Tax Shift”: Labour → Less Distortive Bases

Policy package

Cut employee SSC / PIT for low–middle earners (“make work pay”).

Finance it via a mix of:

base broadening (remove inefficient tax expenditures),

better capital income taxation / closing gaps (as designed),

stronger pricing of environmentally harmful activities,

optionally more recurrent immovable property taxation (with equity safeguards). (OECD)

DWL channel

Reducing the labour tax wedge increases labour supply/participation and formal employment—Belgium remains among the highest in the OECD. (OECD)

Indicative impact (order of magnitude)

Target: -2 to -5 percentage points in the average tax wedge over 3–5 years.

DWL reduction: typically medium-to-large, because labour taxes are among the most distortionary.

Simple schematic

Employer cost (w+c) ↑

| S (after tax)

| /

| / DWL triangle shrinks

|/___

+----------→ Employment

D (net wage)

2) Activation & Benefit-Taper Reform (“Remove Participation Traps”)

Policy package

Smooth benefit withdrawal rates (avoid sharp cliffs).

Expand/retarget in-work benefits (“work bonus”) and simplify eligibility.

Tighten pathways that keep people out of the labour force while protecting those with genuine limitations. (OECD)

DWL channel

When the effective marginal tax rate (taxes + lost benefits) is too high, people rationally avoid additional hours or formal jobs → lost mutually beneficial employment matches.

Indicative impact

High potential in Belgium because labour participation/incentives are a recurring concern in OECD/IMF assessments. (OECD)

3) SME/Startup Simplification “One-Stop Compliance” (Regulatory DWL)

Policy package

Reduce administrative load by:

standardised reporting,

single digital interface for payroll/VAT/social declarations,

fewer “micro-rules” and exceptions (base broadening + simplification). (OECD)

DWL channel

Complex compliance increases fixed costs → fewer firm entries, less competition, lower output.

Indicative impact

Medium, but politically feasible because it can be framed as “simplify without cutting protections”.

4) Housing Supply Reform: Permits, Zoning, and Build-to-Rent

Belgium’s housing affordability issues have a strong supply-side component in urban areas; slow/complex permits are a documented barrier in Brussels, and EU-level analysis stresses that supply reforms are essential (demand subsidies alone often inflate prices). (OECD)

Policy package

Shorten and standardise permit timelines (“silence = approval” for specific categories).

Densification around transit; reduce unnecessary procedural steps.

Stable framework for build-to-rent and renovation, with targeted social housing where needed.

DWL channel

Artificially constrained supply → fewer transactions than efficient equilibrium, misallocation (people living in the “wrong” place/size), and productivity losses from commuting/friction.

Indicative impact

Medium-to-high over time (slow burn, but large cumulative effects).

Schematic

Price ↑ Supply constrained (steeper)

| /

| /

| / shortage / lost trades (DWL)

|_/__________→ Quantity

Demand

5) Pension / Effective Retirement Age Reform (Labour Supply at the Top End)

The IMF and other institutions have emphasised raising the effective retirement age and adjusting eligibility regimes to support labour supply and fiscal sustainability. (IMF)

Policy package

Incentivise longer careers (bonuses) and reduce early-exit distortions.

Harmonise special regimes where feasible, protecting genuinely strenuous occupations.

DWL channel

Early exit can create labour shortages and reduces output—particularly costly in ageing economies.

Indicative impact

Medium, with strong long-run benefits.

6) Shadow Economy Reduction: Make Formalisation Easier (Not Just Enforcement)

Belgium has policy frictions around payments and informality; while not all informality is “pure DWL,” lower informality generally improves allocation, competition, and tax neutrality. (law.kuleuven.be)

Policy package

Reduce incentives to go informal (scenario 1 & 3).

Targeted e-invoicing / real-time VAT reporting in high-risk sectors (phased, support for SMEs).

Enforcement where necessary, but paired with simpler compliance.

DWL channel

Less informality → more scale, financing, productivity, and fewer “wasted” avoidance costs.

Indicative impact

Medium, but complementary and reinforcing.

A pragmatic “3-lane” reform program

Lane A (Fast, 6–18 months): highest feasibility

SME simplification

Benefit taper smoothing / activation adjustments

Targeted compliance digitalisation (NBB)

Lane B (Structural, 1–3 years): biggest DWL reduction

Revenue-neutral tax shift away from labour

Pension/retirement incentives (IMF)

Lane C (Long horizon, 2–5 years): housing supply

Permit reform + zoning/densification + build-to-rent (OECD)